Modern ransomware attacks often greatly affect civilian life and government operations, it is a geopolitical issue.

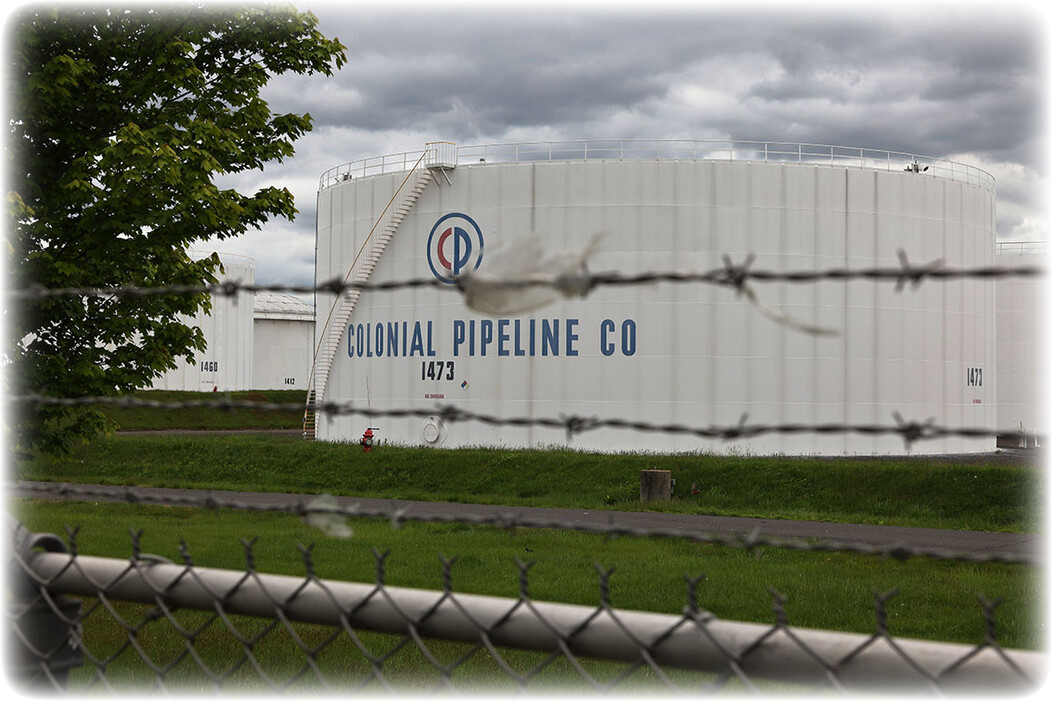

Fuel holding tanks are seen at Colonial Pipeline's Linden Junction Tank Farm on May 10 in Woodbridge, N.J. | Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

Fuel holding tanks are seen at Colonial Pipeline's Linden Junction Tank Farm on May 10 in Woodbridge, N.J. | Michael M. Santiago/Getty ImagesIN 2017, A POWERFUL CYBER WEAPON disrupted “Constitution Day”, a holiday in Ukraine which celebrates the country’s adoption of an independent constitution. Under the noise of fireworks, a silent worm spread silently through the country’s computer systems disabling radiation safety systems at the Chernobyl site, shutting down banks and ATMs, disrupting businesses, maiming the Ukrainian electrical power grid and shutting down metro networks. The worm would pivot into every crevasse of operational technology it could touch and as industrial equipment operators sat behind their control panels, left in an impossible dark, they watched helplessly as the soon familiar skull illuminated their terminal screens, notifying them that their computer’s hard drive had been encrypted and demanding a cumbersome extortion. The scenario was familiar, and the symptoms of the attack looked identical to that of a known ransomware strain, Petya. It was NotPetya.

One of the longest and most worrisome aspects of wormable cyberweapons has always been their ability to spread and consequentially, their inability to be effectively restrained by operators. Soon NotPetya left the confines of the borders it was meant to attack and caused billions of dollars in collateral damage across the international community. It maimed shipping conglomerate MARESK, health care systems and banks across the world, in addition to a wide array of other services civilian life has become attuned to.

It was later revealed that NotPetya was different in comparison to other strains of ransomware. Foremost, it did not actually aim to achieve any financial objective, in fact its encryption algorithm had been modified to disallow decryption. More interestingly however, is the widely accepted prospect that it was created and deployed, by Russian intelligence services. The attribution of NotPetya being developed by the Kremlin has been researched thoroughly by many security companies and can be backed by a trove of digital forensic evidence. How can then, Russia face almost no condemnation or punishment from the international community? It is largely due to the very inability to attribute such an attack, regardless of the evidence supporting it.

Criminal ransomware operators tend to extend the same reach and take advantage of this new unregulated domain. Many, although not all, operate safely within the walls of Russia, under a mutually beneficial safe-harbor principle. As seen with the GRU operatives that operated NotPetya, many are indicted, but never see justice.

There has been no criminal enterprise in recent memory that matches the lucrative nature, reach and financial incentive that ransomware has demonstrated. Cybercrime has long been an attractive facet for financially motivated criminals and their targets have only been growing in terms of size and power. Though in choosing to victimize such targets, these attackers also victimize a larger, associated population. As governments begin to rely more heavily on network-exposed computers to operate on critical infrastructure, it is no wonder why these systems have become targets. Additionally, it is no wonder why large private sector companies, of which civilian life might rely on, are also targeted.

This criminal enterprise operates in a domain that is under-regulated and expands far beyond borders. They are groups of people that the effected government cannot directly prosecute or take easy initiative against, as they would be able to with a domestic threat and so most of the time resort to issuing indictments more as a geopolitical statement. As this threat continues to grow at a rate that is nearly exponential, one must wonder if the action that needs to be taken should be at an international level, rather than a local one. And indeed, ransomware has been shaping the geopolitical landscape for some time, demanding a need for policy change and international cooperation. Moreover, what effects, specifically, do ransomware gangs have on international politics and policy?

Ransomware gangs can sometimes have the impact of a state-sponsored cyber-attack, even if they are anything but. On this facet, they are not purely an issue of domestic law enforcement, even if they are regionally operating criminals. The lack of widely accepted response to these complex issues regarding criminal attacks, state sponsored attacks and safe harbor have only exasperated the problem. The only appropriate response that would prove to be truly effective would be that of international policy creation, expected response, systems for attribution and the instantiation of larger ransomware task forces. Moreover, in order to truly grasp the scale of this threat, it would prove beneficial to examine its effects on civilian life.

There are two primary impacts ransomware at this scale can have, both of which are financially damaging and almost always have unpredictable effects on a country’s economy. However, one has a more obvious and plaintive effect on civilian society while the other is more impactful on private sector entities and entities that may rely on them. Both, however, are attacks to civilian society and governments from a foreign threat, regardless of if they originate from financially motivated criminals.

Type one involves infecting a private sector company which is heavily involved in some industry and whose services are widely used within said industry. Type two involves all the implications of type one with the addition of this service being a crucial civilian service or negatively implicating critical infrastructure in some way. Notable examples of both would include the Cognizant incident (type one) and the Colonial Pipeline incident (type two).

Regarding type one, cyberattacks that have devastating effects on an industry can be seen reflected on an economy. According to a public survey conducted by Sophos, “larger organizations reported a greater prevalence of attacks, with 42% of the 1,001-5,000 employee group admitting to having been hit.” This shows that groups are targeting larger companies which may have supply-chain impact on an industry if infected. Cybercrime magazine states that, “Ransomware will cost its victims more around $265 billion (USD) annually by 2031, Cybersecurity Ventures predicts, with a new attack (on a consumer or business) every 2 seconds.” The influence this could have on a country’s economy is undeniable and the effects on private sector industries have already become unprecedented.

Regarding type two, attacks on critical infrastructure and civilian services can pose a very real national security risk. An example that jumps to mind for most is the WannaCry infections of the NHS. According to FBI Cyber Division, “These types of cyberattacks can impact the physical safety of American citizens” in reference to ransomware attacks which implicate medical and response services. This poses a national security and more prevalently, a homeland security threat. In 2018, a subsidiary to the Department of Homeland Security was instantiated, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), which issues advisories and responds to these threats. As seen on StopRansomware.gov, ransomware has had and frequently does have great ramifications on critical infrastructure. The widespread impact on national and homeland security ransomware poses implicitly involves the question of international change.

The U.S. Department of Treasury believes that illicit payments ransomware groups receive can be used to, “undermine U.S foreign policy and national security interests” and has been implicating sanctions on named ransomware groups to make such payments illegal in many circumstances. The BBC reported, “new analysis suggests that 74% of all money made through ransomware attacks in 2021 went to Russia-linked hackers.” Particularly much of the international community has communicated the threat of Russian cyber to their private sector organizations. Although many criminal ransomware groups originate from Russia, there has also been attribution to the Kremlin itself, such as offensive military operations conducted by the Federal Security Service (FSB).

Since the 2022 invasion of Ukraine, many ransomware groups have pledged their support of the Russian government and even assisted via cyberattack. CISA notes in their advisory, “These Russian-aligned cybercrime groups likely pose a threat to critical infrastructure organizations primarily through: Deploying ransomware …” Events such as these beg the question, are these groups truly acting upon their own volition? Possibly. But many speculate that there may also be loose affiliations with the Kremlin.

It is well known that the reason most notable ransomware groups are Russian is because the Russian government provides safe haven for these groups, so long as they do not attack domestic targets. However, could some of these groups be more deeply affiliated with the Kremlin? There is no direct way to attribute such a claim, but evidence can be scrutinized and speculated upon to reveal patterns which may support this theory.

It is apparent that a great majority of the major Russian based ransomware groups support the Kremlin on the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Specifically, the criminal threat actors known as Conti and Trickbot, respectively. Although these groups are criminal cells, suspiciously, their recent actions have been greatly aligned with what would benefit the Russian government. Recently Bellingcat, a Netherlands journalist group, leaked chatlogs from Conti operators, confirming some sort of link that the criminal group is acting on directives of Russian intelligence services. Similarly, the treasury department confirmed their belief that Trickbot was also state-sponsored noting that, “Trickbot Group’s preparations in 2020 aligned them to Russian state objectives and targeting previously conducted by Russian Intelligence Services.” Let it be known that there is a substantial difference between deniable safe-harbor and direct sponsorship. Between inaction against an unsanctioned action and sanctioning the action yourself. Ignorance only works when you are completely divisible from what you’re feigning it against. Yet, allegedly, these criminal groups are operating under the influence of the FSB with no consequence to either entity.

The majority of cyberwarfare is murky water and largely undefined. Article 2(4) of the UN Charter defines a use of force to be when a state enacts a threat or use of force, “against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state” and which is “significant enough to affect state security.” This violation applies to any use of force, regardless of the agent it was employed via. However, many argue the specific implications of what classifies a use of force violation under international law. Only a minority of states consider cyber operations, or any non-kinetic altercation for that matter, to classify as a use of force violation. Moreover, most cases of use of force are notable in their immediateness of the effects. Due to these two factors ransomware may not be, or at least largely not seen as, a use of force violation.

Many nation-states incorporate their own specific stances and definitions on due diligence. More generally however, it is recognized as an “obligation not to allow knowingly its territory to be used for acts contrary to the rights of other States.” Due diligence is seen as an obligation in international law and acts as a formal expectation of polite behavior. Unsurprisingly, Russia’s safe harbor practice in association with ransomware groups is seen as defiant and uncompliant in this aspect.

It is undeniable that ransomware has had impacts that greatly affect the operation of governments, companies and civilian society. When a problem as such arises, in a domain where many that who have power to make change, are largely unfamiliar, it is unsurprising that the consequence is a continued increase of attacks, extortion and expansion of criminal enterprise. Ransomware is a new and unique issue, where threat groups operate safely behind the confines of their borders, a state response as well as international law enforcement can only do so much. The only truly appropriate response includes international cooperation and diplomacy. Only when the world starts to adopt a stance, define the rules of cyberspace and engage in progressive policy creation and defined responses, will we truly make a mark in the battle against ransomware.