Running a CTF that Outlasts a Bag of Popcorn

Tales and experiences from running PatriotCTF 2023.

My tales and experiences from running PatriotCTF 2023.

Table of contents

Foreword

Running a CTF is hard. Very hard. It involves a lot of moving parts and interacting with technology in a way that is considerate and thorough, even if you are not familiar with it. A lot can go wrong at every step — and frequently, a lot does. In acknowledgment of this, I decided to upload this post to make sure that future organizers of PatriotCTF (and their successors) have a reference for the issues their not-so-distant ancestors encountered.

For context, last weekend was Mason Competitive Cyber’s annual capture-the-flag competition, PatriotCTF, and it was our turn to run it. Prior to this event, no one on the active exec board had substantial experience with infrastructure or sysops. Considering this, the event ran extremely well with very few hiccups.

PatriotCTF was hosted on AWS using CTFd. Our infrastructure was staged on two servers — one hosting the main CTFd instance and another hosting challenge remotes (c6a.2xlarge). Cloudflare was used for reverse proxying and providing subdomains for challenge remotes.

We also had help from a very talented alumni, Christopher Roberts, who came in clutch with two awesome VM reversing challenges and an ARM pwn.

Hack-proof Hacking Challenges

All remotes were containerized using Docker. For the pwn challenges, we used redpwn/jail, and for other remotes, we mostly relied on xinetd.

Redpwn/jail is an nsjail-based Docker image for pwnables, providing isolated, forked, and highly configurable containers. The challenge binary is mounted into /srv/app/run, which is executed inside the jail. Each connection runs in its own forked process that terminates upon disconnection.

Best practice is to pull from a real OS image (e.g., Ubuntu) and copy it into the root directory since the base redpwn image is minimal. Redpwn also allows jail configuration through environment variables. For instance, JAIL_TIME can limit session timeouts, and JAIL_CONNS_PER_IP restricts connections per IP.

Here’s an example Dockerfile from the bookshelfv2 challenge:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

FROM pwn.red/jail

ENV JAIL_TIME=60

ENV JAIL_CONNS_PER_IP=10

ENV JAIL_PORT=8989

ENV JAIL_SYSCALLS=accept,accept4,...

COPY --from=ubuntu / /srv

COPY bookshelf /srv/app/run

COPY flag.txt /srv/app/flag.txt

It really is as simple as that. More examples can be found in the PatriotCTF 2023 challenge repository.

Intended Unintendeds

All challenges should be extensively tested — especially the hard ones. A single unintended solution can compromise the integrity of the entire scoring system.

Organizers should ensure that someone other than the challenge author blind-solves hard challenges in a testing environment. They are more likely to find unintendeds than the author, who knows the intended path.

An unintended solution isn’t always catastrophic unless it’s significantly easier than the intended path.

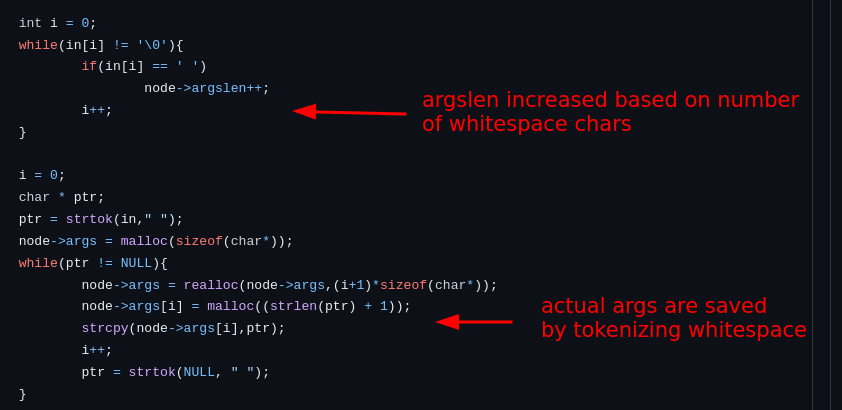

For example, my hard heap grooming challenge, Softshell, was intended to transform an arbitrary free into an arbitrary write. The arbitrary free resulted from a subtle difference between how the program calculated a command list versus its size.

Because the program freed memory based on argslen (which could exceed the actual list size), we ended up with an arbitrary free. The intended exploit required grooming the heap, creating a UAF on a future command’s tag list, and using the edit-tag command to get a write-what-where primitive.

However, an unintended UAF in command arguments let players bypass this complexity entirely. This made a supposedly “insane”-rated challenge unexpectedly solvable by many.

Luckily, some competitors still solved it the intended way — a great writeup is available here.

The Final Hour

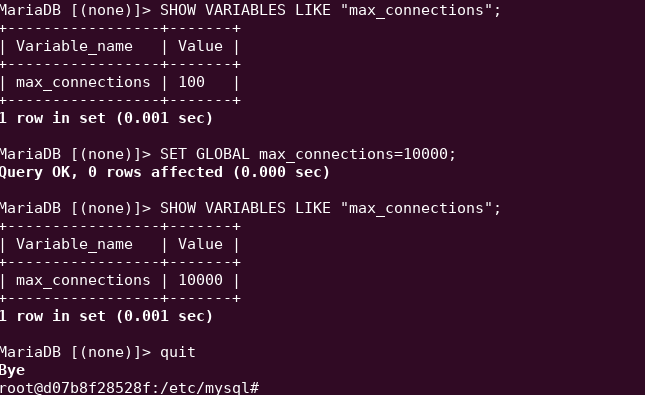

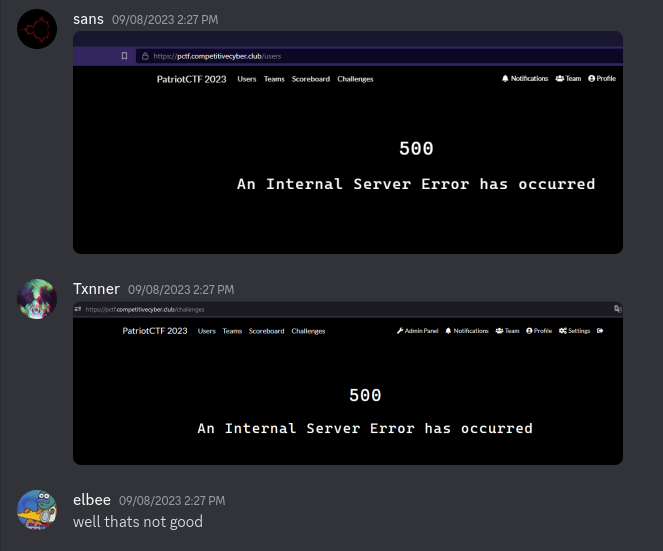

It’s Friday afternoon — everything’s running smoothly until 45 minutes before the competition begins. Suddenly, this happens:

The number one rule for hosting a CTF:

If nothing seems wrong, it just means you don’t know what’s wrong yet.

Something will go wrong. There are simply too many moving parts to account for everything. Instead of expecting perfection, the best approach is to plan for failure — fix what you can and have mitigation strategies ready.

Thankfully, this particular issue was resolved with a simple fix — a quick value edit in the live CTFd SQL database.

Later, we faced downtime on the challenge server. All challenge remotes were containerized on the same machine, which eventually crashed due to a memory leak in the ML PyJail challenge. The server went down during day two at 4 A.M., but our president was awake and managed to diagnose and restart it within 15 minutes.

While the downtime was minimal, the ticket system exploded with caffeine-fueled complaints. In hindsight, we could’ve prevented this entirely by setting Docker memory caps or isolating high-load challenges onto separate servers.

Postface

Hopefully, this gives insight into what goes into hosting a CTF and the unexpected challenges that can arise.

Hosting a CTF is fun, rewarding, and a great way to give back to the security community. There’s nothing like watching people solve challenges you built — sometimes even in ways you didn’t expect.

If you’re considering organizing one: just do it. The experience is invaluable. Learn from our mistakes, plan for chaos, and you’ll have fewer things to worry about when the popcorn burns.

See you all next year for PatriotCTF 2024.